By David Colapinto

Many people still remember that there was “something like a general strike” at Boston University (B.U.) in the Spring of 1979. If you attended B.U. or worked there that’s exactly what it felt like. Over 400 faculty members went on strike in April of 1979 after the B.U. Board of Trustees reneged on a deal to approve a contract. A few days after the faculty started walking picket lines, the B.U. librarians and staff also walked out, striking for recognition of their own unions.

However, when the faculty strike was settled, the librarians and staff were left walking the picket lines on their own and the controversy on campus was far from over. A few faculty members decided to show solidarity with the staff and librarian strikers by holding classes outside or off-campus. That’s when B.U. President John Silber escalated the fight.

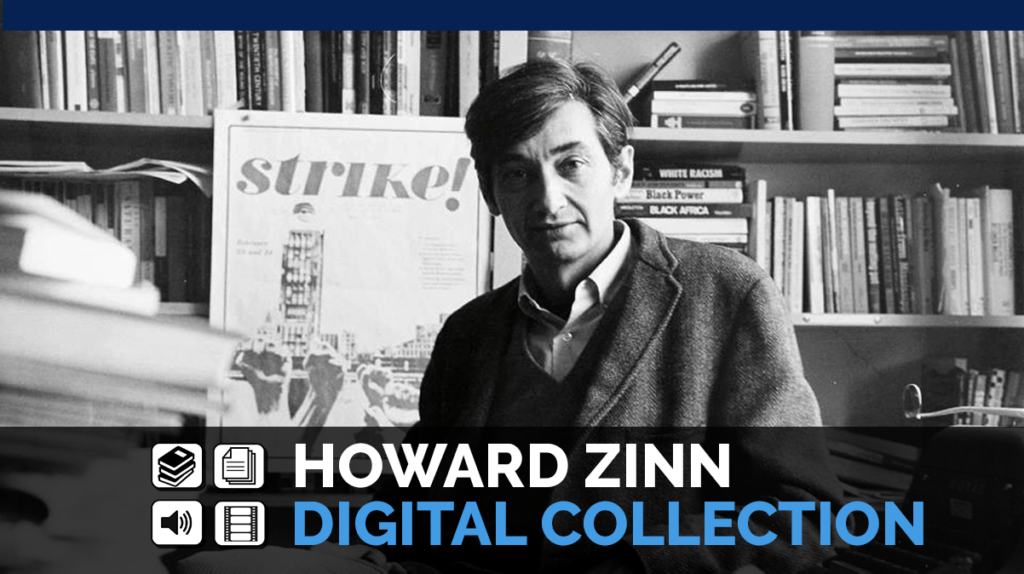

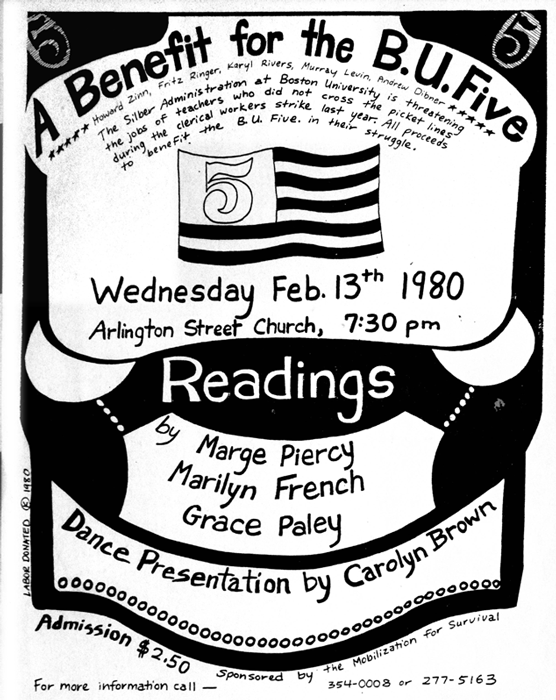

The “B.U. Five,” as they came to be known, were highly respected B.U. professors Murray Levin, Fritz Ringer, Andrew Dibner, Caryl Rivers, and Howard Zinn. All five were active in the faculty union. Ringer was president of the B.U. chapter of the faculty union and Zinn was co-chair of the faculty strike committee.

None of the B.U. Five wanted their students to have to cross the librarian and staff picket lines in order to attend classes, so their classes were held at different locations.

Silber acted swiftly to terminate these faculty union activists whom he viewed as troublemakers. The B.U. Five’s alleged infraction was violating the newly ratified faculty union contract, “which prohibited ‘sympathetic strikes.’”

When the next academic year began in the Fall of 1979, B.U. pressed ahead with proceedings to terminate and remove the B.U. Five from the faculty, despite their tenure.

In November of 1979 Silber upped the ante by declaring that the B.U. Five “were trying to destroy the university from the inside.” The following month the B.U. faculty union filed a grievance alleging that B.U. was violating the union contract by attempting to “coerce, harass and annoy” the faculty’s right to academic freedom through the proposed terminations of the B.U. Five.

Zinn was a veteran of the civil rights and anti-war movements and edited Justice in Everyday Life: The Way It Really Works among his many books. He understood the limits of the justice system and was a life-long advocate for organizing public pressure to achieve social justice. Zinn knew that the battle for public opinion was essential for the B.U. Five to prevail against Silber and that was as important, if not more so, than what happened in the union grievance proceedings. The struggle facing the B.U. Five would put this to the test.

Instead of returning to labor peace after settling the faculty strike, Silber’s proposed firing of the B.U. Five was an overreach at best and set off a firestorm of protests calling for Silber’s own removal. For Silber, the trumped-up charges against the B.U. Five at first must have seemed like an ironically delicious way to settle a score with union activists and with Zinn, in particular, who Silber long despised. But Silber miscalculated.

In the months that followed, Zinn led an ad-hoc “Committee to Save B.U.” that was composed of faculty, students and staff who urged that B.U. remove Silber, and a nationwide anti-Silber campaign was organized to support the B.U. Five. Nobel laureates circulated a petition that was signed by 500 faculty members in the Boston area calling for Silber to be fired and for academic freedom at B.U. to be restored. Outrage poured in from other faculty across the country and from B.U. alumni.

The Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts also issued a report highly critical of B.U.’s repression of academic freedom and freedom of expression.

On campus, student groups organized to support the B.U. Five. The College of Liberal Arts (now the College of Arts and Sciences) student government voted 11-1 to donate funds to the B.U. Five’s defense. Students also sponsored a teach-in to raise more funds where they heard from the B.U. Five and others, including Daniel Ellsberg, the Pentagon Papers whistleblower, who spoke at that event.

Throughout the Fall of 1979, the organized protest of Silber’s retaliation against the B.U. Five had picked up steam and morphed into a full-blown movement calling for Silber’s removal. In December of 1979, the B.U. faculty voted overwhelmingly, 456 to 215.5*, to remove Silber as B.U. President. [See WGBH coverage of the vote, including an interview with Zinn starting at 2:30, via Open Vault.]

Professor Helen Vendler, one of the authors of the petition to remove Silber, accused him of creating a “reign of terror within the university.” At the height of the B.U. Five controversy, Silber even falsely accused Zinn of being involved in arson of a campus building years earlier—a false comment for which Silber publicly apologized at the B.U. faculty meeting.

In January of 1980, the television show 60 Minutes broadcast a somewhat flattering profile of Silber, calling him the “Bad Man On Campus.” But the program also aired criticism of Silber’s attacks on academic freedom and civil liberties and claims that Silber may “have benefited financially from risky investments he had convinced the Board of Trustees to make,” which led to other investigations questioning his financial relationships.

Shortly after the national media attention and faculty uprising against Silber, the university caved and agreed to drop its charges against the B.U. Five. Silber’s gambit to get rid of Zinn and four other pro-union faculty members had backfired.

B.U. student activists like me who had a ringside seat learned many things from the B.U. Five controversy that were not offered in the course catalog. For example, organizing public pressure works. So does standing up to bullies who wield power like tyrants. We were lucky to have Howard Zinn teach us those lessons.

David Colapinto was a B.U. student in 1979-80 and is an attorney at Kohn, Kohn, & Colapinto in Washington, D.C. with expertise in whistleblower and qui tam cases. He also co-founded the National Whistleblower Center. Here are more of Colapinto’s memories of having Howard Zinn as a professor.

* Note the fraction of a vote (0.5) is because, according to The New York Times, the votes were tallied “under a system in which full‐time faculty members were accorded one vote each and halftime and unpaid honorary faculty members were given half‐votes.”