Spelman College girls are still “nice,” but not enough to keep them from walking up and down, carrying picket signs, in front of supermarkets in the heart of Atlanta.

By Howard Zinn and Paula J. Giddings • The Nation • March 23, 2015

This article is part of The Nation’s 150th Anniversary Special Issue. Download a free PDF of the issue, with articles by James Baldwin, Barbara Ehrenreich, Toni Morrison, Howard Zinn and many more, here.

This article is part of The Nation’s 150th Anniversary Special Issue. Download a free PDF of the issue, with articles by James Baldwin, Barbara Ehrenreich, Toni Morrison, Howard Zinn and many more, here.

Finishing School for Pickets

By Howard Zinn • First published in The Nation • August 6, 1960

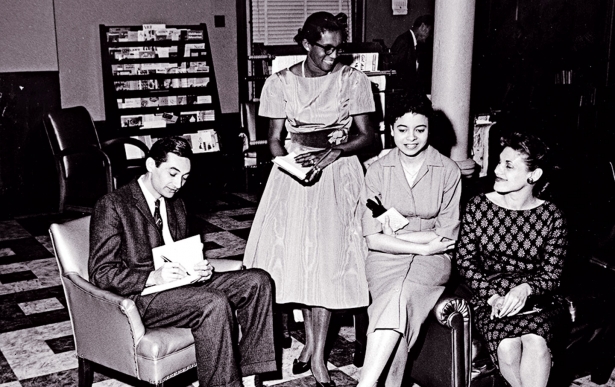

One afternoon some weeks ago, with the dogwood on the Spelman College campus newly bloomed and the grass close-cropped and fragrant, an attractive, tawny-skinned girl crossed the lawn to her dormitory to put a notice on the bulletin board. It read: Young Ladies Who Can Picket Please Sign Below.

The notice revealed, in its own quaint language, that within the dramatic revolt of Negro college students in the South today another phenomenon has been developing. This is the upsurge of the young, educated Negro woman against the generations-old advice of her elders: be nice, be well-mannered and ladylike, don’t speak loudly, and don’t get into trouble. On the campus of the nation’s leading college for Negro young women—pious, sedate, encrusted with the traditions of gentility and moderation—these exhortations, for the first time, are being firmly rejected.

Spelman College girls are still “nice,” but not enough to keep them from walking up and down, carrying picket signs, in front of supermarkets in the heart of Atlanta. They are well-mannered, but this is somewhat tempered by a recent declaration that they will use every method short of violence to end segregation. As for staying out of trouble, they were doing fine until this spring, when fourteen of them were arrested and jailed by Atlanta police. The staid New England women missionaries who helped found Spelman College back in the 1880s would probably be distressed at this turn of events, and present-day conservatives in the administration and faculty are rather upset. But respectability is no longer respectable among young Negro women attending college today.

“You can always tell a Spelman girl,” alumni and friends of the college have boasted for years. The “Spelman girl” walked gracefully, talked properly, went to church every Sunday, poured tea elegantly and had all the attributes of the product of a fine finishing school. If intellect and talent and social consciousness happened to develop also, they were, to an alarming extent, byproducts.

This is changing. It would be an exaggeration to say: “You can always tell a Spelman girl—she’s under arrest.” But the statement has a measure of truth.

[This is an excerpt from the full length version of Finishing School for Pickets.]

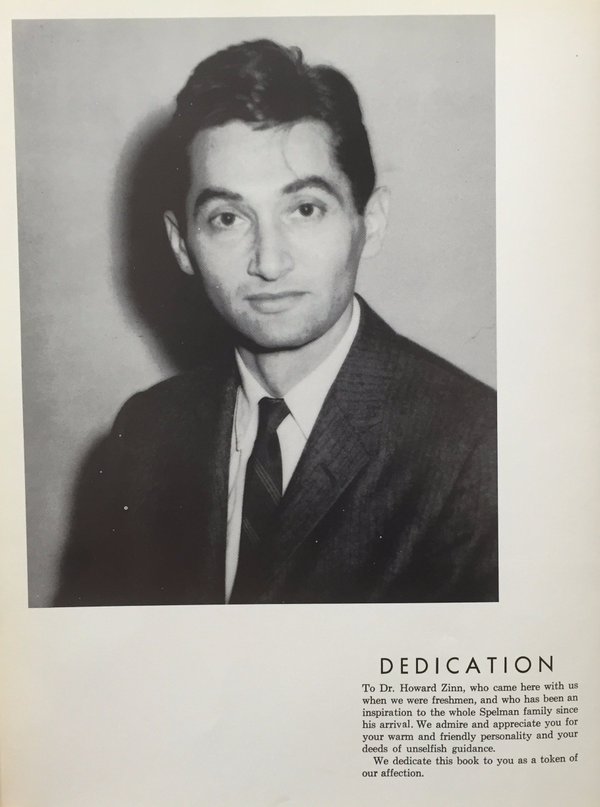

Howard Zinn (1922–2010) wrote for The Nation from 1960 to 2008; the articles are collected in Some Truths Are Not Self-Evident: Essays in The Nation on Civil Rights, Vietnam and the “War on Terror,” published by eBookNation last year.

* * *

Learning Insubordination

By Paula J. Giddings • Published in the April 6, 2015 issue of The Nation

In the current age of “lean-in” feminism at one end of the spectrum and an “anti-respectability” discourse at the other, the late Howard Zinn’s essay reminds us of an earlier meaning of women’s liberation.

Zinn was of Russian-Jewish heritage, an influential historian and, in 1960, a beloved professor at Spelman College, the historically black women’s institution in the then-segregated city of Atlanta. The attribution of “finishing school” in the title was well-earned: Spelman girls, whose acceptance letters included requests to bring white gloves and girdles with them to campus, were molded to honor the virtues of “true-womanhood”: piety, purity, domesticity and submissiveness.

Nevertheless, by 1960, Zinn’s students had morphed from “nice, well-mannered and ladylike” paragons of politesse to determined demonstrators who picketed, organized sit-ins, and were sometimes arrested and jailed for their efforts. “Respectability is no longer respectable among young Negro women attending college today,” Zinn concluded.

These young girls were born in the 1940s, and whatever the background of their parents (who might be sharecroppers, teachers or doctors), their generation was destined to belong to a new stratum of Americans: the “Black Bourgeoisie,” as the sociologist E. Franklin Frazier called it. An economic class that was literally wedged in the “middle” between a small black elite and the black masses, this group emerged in no small part because of the unprecedented number of educated women who, historically excluded from pink-collar positions, now had access not only to the elite professions, but to mainstream administrative, clerical, and civil-service jobs.

For black women, burdened by stereotypes of hypersexuality, this development meant more than a triumph of simple social mobility. With education, more girls could now escape the domestic and personal service work that subjected them to the sexual exploitation of employers and others. To be able to avoid such a soul-killing future was the dream of generations of mothers for their daughters—one that I often heard from my own grandmother, who had migrated north so that my mother could be the first in the family to attain a college education. The stakes in taking advantage of these newer opportunities were indeed high and brimmed with profound meaning and emotion.

In 1960, Spelman, like other black schools—including those that educated and employed the great civil-rights lawyers and intellectuals of the period—had little tolerance for the student activities that Zinn encouraged and sometimes led. It was one thing to support integration and equality, and quite another to sanction a sit-in at the segregated library or enrage powerful politicians by occupying the whites-only visiting section of the Georgia legislature. Although these acts were not as dramatic as the more violent encounters that we are familiar with, these young women were also risking their lives. Expulsion, the loss of a scholarship or a work-study opportunity, could mean an end to the hopes of a relatively secure—and protected—future.

Nevertheless, this was the Spelman generation that included students like Ruby Doris Smith Robinson, a former debutante who understood that the long-term future of others was more important than her own immediate well-being. She dropped out of college to join the Freedom Rides; became a leader of the “Jail, No Bail” movement; and was the first woman to head the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the premier youth organization.

Feminists today might consider Zinn’s insight that his “nice, well-mannered and ladylike” students did not so much abandon respectability as redefine it. They recognized a moment when virtue required acting out, not leaning in, and when the corrective for stifling mores were not displays of unfettered individual behavior that reinforced dangerous stereotypes.

Former Spelman students Alice Walker, the Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist, and Marian Wright Edelman, founder of the Children’s Defense Fund, credit Zinn as being key to their own activist transformations. The kind of history he wrote and taught intellectualized traditions of black resistance and, as Edelman recalled, encouraged them “to think outside the box and to question rather than accept conventional wisdom.” For Walker, despite her perennial fear of losing a needed scholarship, the fact that Zinn not only supported but participated in student demonstrations encouraged her to “carry on” despite the risk.

The professor was also taking a risk, and in 1963 he was fired from Spelman for insubordination. “I plead guilty,” he responded with pride, and in the end both students and teacher were better for the experience. In an interview, Zinn once said that his years at Spelman were “probably the most interesting, exciting, most educational years for me. I learned more from my students than my students learned from me.”