By James Green • May 23, 2003

By James Green • May 23, 2003

The Chronicle of Higher Education

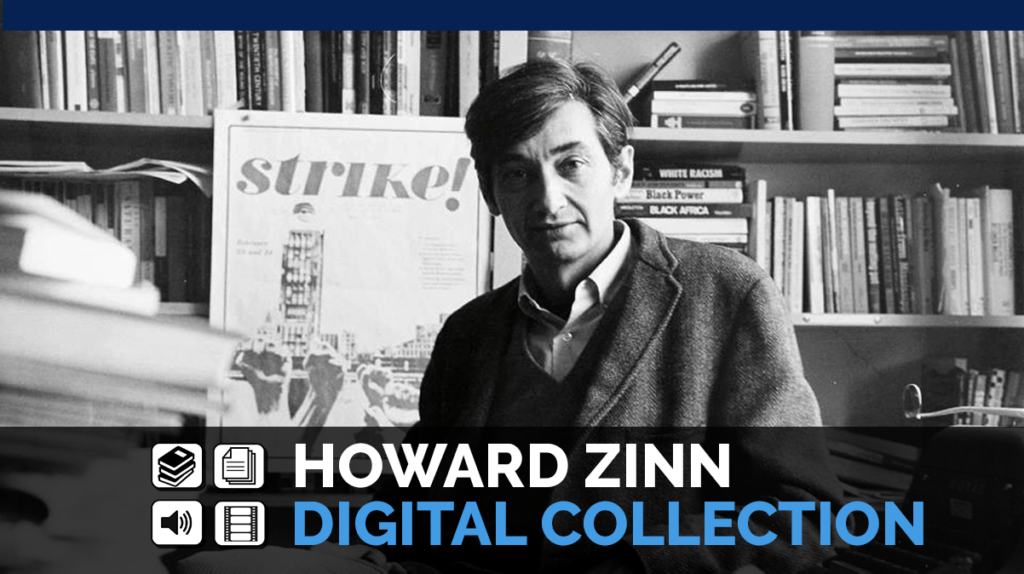

A sellout crowd filled the 92nd Street Y in New York recently to celebrate a publishing milestone: the sale of one million copies of Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States. First published in 1980, the book, updated by the author, continues to be assigned in countless college and high school courses, but its commercial sales have remained strong as well. It is probably the only book by a radical historian that you can buy in an airport.

Zinn’s editor at HarperCollins, Hugh Van Dusen, says the book is unique in his 40-plus years of publishing: For two decades, it has sold more copies each year than it sold the year before. Last year it sold 128,000 copies.

The people who gathered in New York to hear readings from A People’s History by James Earl Jones, Danny Glover, and others were celebrating more than a book, of course. They were celebrating a person—someone a former student, the novelist Alice Walker, called “this unassuming hero, this people-loving ‘trouble maker.’ ”

At 80, Zinn is not only a best-selling author but remains a tireless crusader for peace and justice, and a public speaker who is in more demand than ever. His credibility and authority as a social critic stem in part from the sincerity and longevity of his commitment to radical thought and action.

Zinn’s older books and pamphlets, now reissued in South End Press’s Radical 60s Series, offer evidence of his outstanding history as a chronicler and interpreter of social protest, and as a critical thinker and radical writer beginning in his Atlanta days with the Civil Rights Movement—experiences he recorded in two passionate books published in 1964: The Southern Mystique and SNCC: The New Abolitionists. They remain some of the best observations we have of the courage and intelligence of the youthful Black freedom fighters in the South.

Zinn’s leading role as a critic of U.S. military and foreign policy is embodied in his Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal (1967), a tightly reasoned book that went through eight printings in a year. Zinn’s charismatic presence as a peace activist, as well as a counselor to Vietnam veterans and draft resisters, emerges from the pages of Disobedience and Democracy (1968), which his new preface describes as a “little book that sold over 70,000 copies and served as a theoretical buttress to the many acts of civil disobedience committed during those years of the war in Vietnam.” And Zinn’s legendary work as a teacher at Boston University is revealed in a remarkable collection called Justice in Everyday Life: The Way It Really Works (1974), in which Zinn, his students, and local activists describe their research projects on police brutality, prison abuse, and court corruption, as well as on poor housing, schooling, and health care.

After his retirement in 1988, Zinn remained very active. Some of his best essays and speeches in recent years appear in a lively collection called Failure to Quit: Reflections of an Optimistic Historian (1993). Here Zinn’s voice seems to echo those of his heroes: the pamphleteer Thomas Paine as he destroys the rationale for royal authority, the resister Henry David Thoreau as he refuses to pay war taxes, the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison as he burns copies of the Fugitive Slave Act and the Constitution. But we also hear Zinn’s own distinctively modern voice, filled with the wit and wisdom he absorbed on the streets of Brooklyn in the 1930s.

Born of immigrant, blue-collar parents, Zinn was raised, he said, in a family always “one step ahead of the landlord.” After the United States entered World War II, he worked in a unionized shipyard until 1943, when he joined the Army Air Corps at age 20. He served as a bombardier on B-17s flying missions over Europe—an experience that would later shake his belief in “just wars.” After the war ended, he married Roz Shechter, who also lived in Brooklyn and shared his passion for reading as well as his “outlook on the world, the war, fascism, socialism,” as Zinn put it in his autobiography.

They lived first in a basement in Bedford-Stuyvesant, then moved to the Lillian Wald housing project on the East Side. There they raised two children while he unloaded trucks at a warehouse and she did office work for a publisher. During this time, Zinn attended New York University and then Columbia University on the G.I. Bill. His first college teaching job took him south to Atlanta and Spelman College in 1956. When he and a group of African-American students protested segregation by sitting in a whites-only section at the Georgia statehouse, a riot nearly erupted. Zinn soon became influential in the Civil Rights Movement and served with Ella Baker as an adviser to the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee.

When Zinn’s students brought their activism back to the campus, he was blamed and fired. He moved to Boston University in 1964, and a year later spoke on Boston Common at that city’s first significant rally against the U.S. military incursion in Vietnam. He became one of the peace movement’s most charismatic and effective leaders, a reputation that endures. Today, he is constantly called upon to speak about the United States’ attack on Iraq.

When Zinn decided to write A People’s History (at Roz’s insistence), the radical movements he had championed were fading and the book’s chances for success seemed slight. Oscar Handlin, a renowned Harvard historian, hated it. In a review for The American Scholar, he wrote sarcastically that the author was “a stranger to evidence.” Not only was the book “anti-American,” Handlin thundered in conclusion, but its author heaped “indiscriminate condemnation on all the works of man—that is upon civilization, a word he usually encloses in quotation marks.”

Handlin’s attack on Zinn betokened a conservative assault on radical scholarship and teaching. Ronald Reagan was elected president during the year A People’s History appeared, and his new cultural commissars, William J. Bennett and Lynne V. Cheney, declared a “crisis in history” created by “ideologically biased” historians whose emphasis on oppression and exploitation in the past was subverting the idea of an American “common culture” with “shared values.”

When speaking of subversives, Bennett probably had Zinn in mind. During the 1970s they had been antagonists at Boston University, where Zinn taught large classes in radical criticism and Bennett protected and defended the college’s president, John Silber, a leader in the conservative attack on activism and multiculturalism in academic life.

Zinn’s A People’s History drew upon the entire corpus of New Left scholarship, a body of work academics like Silber and Bennett despised. Radical historians welcomed the book, but some expressed reservations as well. Eric Foner, a respected historian with leftist sympathies, praised Zinn in a New York Times review for writing “with an enthusiasm rarely encountered in the leaden prose of academic history” and for offering vivid descriptions of protests and movements usually ignored in mainstream history. He thought historians might well view A People’s History as “a step toward a coherent new version of American history,” but Foner also remarked that Zinn’s “bottom up” approach offered a “curiously circumscribed” view of the American past, one in which Zinn portrayed the common people as “either rebels or victims” but rarely as people simply “struggling to survive with dignity in difficult circumstances.”

Despite the chilly climate in which Zinn’s book appeared, A People’s History caught on with thousands of readers. One of them was Bruce Springsteen, who read Zinn in the depressing winter months of 1981-82 as he thought about the suffering he saw in the heartland at the beginning of the Reagan era. Shutting himself off in a rented New Jersey hideaway with his guitar and a tape deck, Springsteen recorded the haunting songs that appeared on his 1982 album Nebraska—bleak poems about the losers in a land of new millionaires.

A People’s History also appealed to readers, especially students, during the 1980s and 1990s because the author countered the conservative culture of the time. Zinn’s symphony for the common people clashed sharply with the martial music of the Republican campaign to revive traditional forms of patriotism and to discredit critical studies of U.S. history and society. For many Americans, reading Zinn became a private act of dissent.

Zinn’s book also met the needs of a hungry audience of teachers who had been students during the Vietnam War era and regarded the author as a hero. A generation of educators who were supporters of the civil rights, antiwar, and draft-resistance movements knew of Zinn not only as a radical critic, but as a courageous activist who took personal risks in his politics. They wanted their students to read his book, especially his impressive accounts of the struggles against segregation in the American South and for peace in Vietnam. And if they were forced to use more-standard textbooks, as most high school teachers were, they wanted an additional counternarrative that would provoke students to think critically about the past, to read beyond the “facts to memorize” approach to history education.

The book’s continued appeal also owes a great deal to its readability. The author confidently surveys more than 500 years of history, drawing deftly on three decades of critical scholarship that reveals the underside of American history that rarely found its way into textbooks before.

Zinn makes no apologies for his selectivity or his subjectivity. He has often criticized the academic illusion of “objectivity”—the myth that scholars write without a point of view. All history, he insists, reflects the interests and values of the historian. He does, however, express some regrets in a recent afterword that the book is not multicultural enough because it slights Latino struggles for justice in the West and offers “minimal treatment of gay and lesbian rights.”

Zinn’s prose shows his flair for describing a human confrontation or sketching a character—a talent he has also displayed in Emma: A Play in Two Acts About Emma Goldman, American Anarchist (1986). He has a journalist’s eye for describing events and choosing an apt quote, as well as a scholar’s ability to use primary sources effectively. And he manages to apply a wide range of historical interpretations without interrupting the flow of his narrative.

Zinn also draws liberally (and with all due credit) upon a rich array of works in the new social history —the scholarship that made history from the bottom up possible. For example, he makes use of the pioneering research on slave resistance by Herbert Gutman and Eugene Genovese and writings on the fierceness of 19th-century class conflict by the labor historian David Montgomery.

Historians of social movements appreciate Zinn’s dramatic evocation of the recurrent and irrepressible struggle for human rights in American history. For instance, he recreates many heroic and often tragic episodes in labor history like the 1914 Ludlow Massacre, in which 26 people, 11 of them children, were killed by National Guardsmen during a strike against John D. Rockefeller’s Colorado Fuel and Iron Company. (Zinn revisited the incident in an essay for the 2001 book Three Strikes.) But Zinn’s celebration of spontaneous protest and heroic acts of resistance left some historians unsatisfied. “Uprisings are either crushed, deflected, or co-opted” in Zinn’s narrative, while “incremental gains, such as those of the 1930s, merely stabilize the system,” wrote Foner, who thought this all reflected “a deeply pessimistic vision of the American experience.”

Zinn does see the dark side of America’s past when it comes to the actions of elites, but he identifies himself as an “optimistic historian” who wrote A People’s History hoping that the “memory of people’s resistance” would suggest new definitions of popular power. “I can understand pessimism, but I don’t believe in it,” he declared in 1990. “It’s not simply a matter of faith, but of historical evidence. Not overwhelming evidence, just enough to give hope, because for hope we don’t need certainty, only possibility.” A People’s History reflects Zinn’s skepticism about government reforms and legal remedies, while at the same time expressing his belief in citizens’ power to effectively resist injustice.

Some teachers say that Zinn’s hopeful message is lost on many students and that his account of crimes against humanity tends to reinforce the sense that “history repeats itself” in tragic ways. It is easy to see why some students remember the victims of oppression in A People’s History more vividly than the heroes of resistance. Zinn is especially effective when he evokes the lost lives of people who stood in the way of Western “civilization.” Even the mature college students I teach are shocked by his first chapter on Christopher Columbus and the destruction of the Arawak people on Hispaniola. Whenever I ask readers about their experience with the book, it is this first chapter they remember. Often, they say: Why didn’t we know this? Why didn’t we learn this in school?

Zinn’s treatment of Columbus is so famous that it found its way into a script of The Sopranos last fall. Tony’s son, A.J., is holding a copy of A People’s History during an argument with his father about whether the man Tony calls “a brave Italian explorer” was really “a hero.” More significantly, nearly every college textbook published during the last two decades now begins, as Zinn did, with the European destruction of the Indians.

The actors Matt Damon and Ben Affleck incorporated A People’s History into their Oscar-winning script for Good Will Hunting (1997). Damon’s character, Will, a working-class genius, trumps a pedantic Harvard student by revealing detailed historical knowledge, and then later tells his therapist (played by Robin Williams) to read a “real book”—Zinn’s A People’s History—a book that “will knock you on your ass.” (Damon and Affleck, who were assigned the book by their high-school teacher in Cambridge, Mass., are currently working with Zinn to create a series of television dramas for HBO drawn from A People’s History.)

While challenging official versions of historical truth, Zinn assumes a moral authority exceedingly rare in professional academic writing. Many readers find this compelling, and, even if they don’t agree with Zinn, they find it refreshing. Here is an author who not only takes sides with those who opposed the U.S. wars with Mexico and Spain in the 19th century, but who also questions the morality and challenges the rationale for World War II and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In his chapter “A People’s War?” Zinn emphasizes the economic and diplomatic interests that determined U.S. war aims rather than moral or humanistic concerns. Behind his critical account of the “good war” lies a critique of the rationale for “just wars.”

In a 1991 speech against the U.S. war on Iraq (reprinted in Failure to Quit), he challenged the way in which pro-war leaders have used World War II as a justification for other military actions. He explained further that while World War II had a “just cause” (the defeat of fascism) that led him to volunteer, the experience of war made him feel that “we had become brutalized.” He came to question whether appeasement and war were the only choices. Surely, he argued, there are “ways of dealing with tyranny and injustice without killing huge numbers of people.”

Behind Zinn’s story of World War II readers can also detect the author’s personal engagement. The reasons for it are revealed in Zinn’s 1994 autobiography, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train: A Personal History of Our Times, in which he offers affecting accounts of his experience as a World War II bombardier and of his later visit to Hiroshima, where he was speechless when asked to talk to survivors.

Many of Zinn’s readers have heard him speak in person. Like his longtime partner in dissent, Noam Chomsky, Zinn is an extremely popular figure on college campuses. He was invited to talk about the coming war against Iraq at Tufts University; in spite of torrential rain, the audience overflowed a large room and listened with rapt attention. His calendar reads like that of a presidential primary candidate. He speaks at high schools, public libraries, radio stations, church meetings, conferences, sit-ins, strikes, and rallies nationwide.

A good deal of Zinn’s appeal as a writer is surely linked to that talent as a speaker. Rousing at outdoor rallies, in a small group he is disarmingly casual, even beguiling. Never speaking from notes, always asking for questions, and then listening to them carefully, Zinn seems deeply troubled by the state of the world and yet remarkably at ease, confident that a gathering of concerned citizens can reflect on the past and find hope for the future. To keep alive the memory of people’s resistance to injustice, Zinn concludes in his A People’s History, “is to find a powerful impulse to assert one’s humanity” and “to hold out, even in times of pessimism, the possibility of surprise.”

James Green (November 4, 1944 – June 23, 2016) was a professor of history and labor studies at the College of Public and Community Service, at the University of Massachusetts at Boston. He authored the book Taking History to Heart: The Power of the Past in Building Social Movements (University of Massachusetts Press, 2000).