On October 11, 2022, Charles Sherrod passed away. Sherrod (January 2, 1937–October 11, 2022) was field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and leader of SNCC’s Southwest Georgia Project in Albany, Georgia. Howard Zinn captured Sherrod’s activism to register people to vote that was met with police violence and federal indifference in the report Albany: A Study in National Responsibility and SNCC: The New Abolitionists. We share these excerpts that feature Sherrod’s dedication to the civil rights struggle. Read more about Charles Sherrod at the SNCC Digital Gateway.

Albany: A Study in National Responsibility

By Howard Zinn • Page 23–25 from • 1962

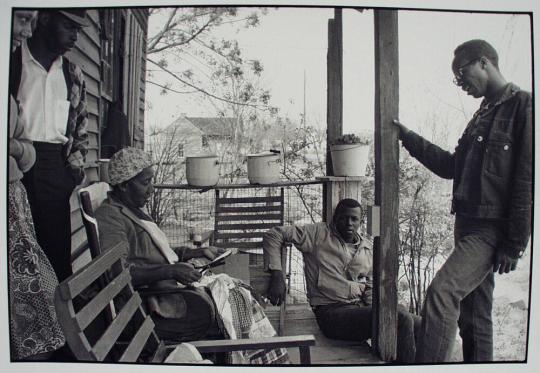

In November 1961, just before the first wave of demonstrations in Albany, SNCC workers Charles Sherrod and Cordell Reagan began a campaign to register Negro voters in Terrell County. They stayed at the home of Mrs. Carolyn Daniel, a young Negro woman who operates a beauty parlor in Dawson. Early in January 1962, police cars began prowling around the Daniel home. The following month, Sherrod, visiting another SNCC worker who had been jailed on a traffic violation, was put into jail for “disorderly conduct.” In March, Sherrod sent out a news release from the SNCC office in Atlanta criticizing “the slow progress of the U.S. Justice Department in following through on complaints of brutality, intimidation, and harassment aimed at Terrell County Negroes.” In April, Sherrod again pointed to intimidation in Terrell County, asking action from the Department of Justice.

At the start of the summer, the tiny SNCC group registering voters in Terrell County was joined by Ralph Allen, a white student from Trinity College, Connecticut. On July 4, he and Joseph Pitts, an Albany student, reported that they were attacked by a white man while talking to Dawson Negroes about voter registration. The man had struck Pitts on the head with a cane and slapped Allen. Complaining to the sheriff, they were referred to Chief of Police W. B. Cherry of Dawson, who was himself involved in the Brazier killing.

Cherry referred them to the sheriff. Wanting to swear out a warrant against their assailant to prevent future attacks, they went to the home of Justice of the Peace Daniel English, who ran out and shouted to Pitts: “Get off my porch, n—–.” The Atlanta SNCC office again asked the Justice Department to act.

On Saturday, July 21, Ralph Allen was walking down Railroad Street in Dawson when a truck tried to run him down. The driver jumped out and said: “You came here to show our n—–s how to vote. I should kill you.” Allen put his hands behind his back in the customary SNCC posture of non-violent response. The man hit him on the side of the head. He put his hands behind his back again.

The man knocked him to the ground and began kicking him. Two others came along, one putting his foot on Allen’s throat, the other kicking him in the side. One drew a knife and said: “Should we kill him now?” They finally let him go. The F.B.I. in Albany was notified of the incident.

The following Wednesday, July 25, a remarkable voter registration meeting took place at the Mount Olive Baptist Church in Sasser, a rural hamlet on the road between Albany and Dawson, in Terrell County. The meeting was reported vividly to the nation by Claude Sitton of the New York Times, Pat Watters of the Atlanta Journal, and Bill Shipp of the Atlanta Constitution. The 40 persons at the meeting consisted mostly of Negroes from the area. Also attending were SNCC workers Charles Sherrod, Charles Jones, Ralph Allen, and Penelope Patch, a 19-year-old Swarthmore college student. As Sherrod was reading from the scriptures, 13 white men, led by Sheriff Mathews and including the sheriff of nearby Sumter County, entered the church. Sheriff Mathews began questioning people, took names, warned Allen to leave the county, told the group it would not be to their interest to continue the meeting, and said to reporters: “We are a little fed up with this voter registration business … we want our colored people to live like they’ve been living for the last hundred years—peaceful and happy.” When the meeting was over, a deputy sheriff said to one Negro leaving the church: “I know you. We’re going to get some of you.” Before going to the Sasser meeting, one of the newsmen had invited the F.B.I. along, but the invitation was declined.

On Sunday, July 29, Ralph Allen and Charles Sherrod were arrested by Sheriff Zeke Mathews while accompanying Negroes to the voter registration office. They spent five days in jail before being released on bond. When Allen asked what was the charge a~ainst them he was told: “Investigation, vagrancy, and all that crap.’ Reporter Bill Shipp of the Atlanta Constitution wrote: “Terrell County Sheriff Zeke T. Mathews refused to let reporters see the warrant on which Sherrod and Allen were arrested. He also refused to show them the docket where the cases had been booked.”

Perhaps spurred by the July 25 incident at Sasser, the Justice Department, on August 13, asked the U.S. District Court to prohibit law enforcement officials from intimidating prospective voters in Terrell County and to halt prosecution of Sherrod and Allen for their recent arrest. Judge Elliott refused to grant an immediate temporary injunction, saying there was no evidence of immediate danger to the civil rights of those involved.

Two days later, a church used as a voter registration center in neighboring Lee County burned to the ground. Two weeks later, the homes of four Negro families active in voter registration were riddled by bullets, which narrowly missed taking the lives of sleeping children. On September 5, a SNCC registration worker was wounded by a shotgun blast in Dawson. And on Sunday, September 9, the same Mount Olive Church in Sasser which had been the scene of Sheriff Mathews’ invasion in July was burned to the ground. As of the writing of this report, Judge Elliott has still not issued an injunction.

SNCC: The New Abolitionists

By Howard Zinn • Excerpt from pages 124 – 126

. . . Charles Sherrod, twenty-two, and Cordell Reagan, eighteen, veterans of the sit-ins, the Freedom Rides, and McComb, arrived by bus in Albany, Georgia, to set up a voter registration office.

. . . Charles Sherrod, twenty-two, and Cordell Reagan, eighteen, veterans of the sit-ins, the Freedom Rides, and McComb, arrived by bus in Albany, Georgia, to set up a voter registration office.

When they stand up in front of a church at a mass meeting, they can stir a crowd to song like no one else. Sherrod is more outgoing; he smiles boyishly when he speaks, his voice is softly resonant, and he lowers it to a vibrant whisper when he wants to emphasize a point about which he feels very deeply. Reagan is quiet, intense, a thin cord of energy and emotions, with the cheekbones and countenance of a Mongol nomad.

Albany was picked for a voter registration campaign for the same reasons Mississippi was chosen: educated Negro youngsters from the border states of the South wanted to return, it seemed, to the source of their people’s agony, to the area which was the heart of the slave plantation system, in order to cleanse it once and for all time. Albany was the old trading center for the slave plantation country of southwest Georgia, and though it was now becoming modern and commercial, and selling more pecans than cotton, it was surrounded by the past. In the counties around Albany blacks outnumbered whites; they worked the land and lived in shacks and didn’t dare to raise a single cry against the rutted order of their lives. Around Albany were “Terrible” Terrell County, “Bad” Baker County; Sherrod added a few appellations of his own — Unmitigated Mitchell, Lamentable Lee.

In Albany itself, Negroes constituted 40 percent of the city’s populations of 56,000 and lived in a tightly segregated society from the cradle to the grave. From the world outside came, in the 1950’s, the first tremors of change: the Supreme Court decision, the Montgomery bus boycott, Little Rock, the sit-ins and Freedom Rides, the emergence of the new black nations of Africa. But in Albany few Negroes voted, and those who spoke up did so quietly, among themselves. By early 1961, a small group of Albany Negroes decided to meet and to present complaints in a petition to the city commissioners. But the mass of the Negro population held back, remained silent. It was this screen of silence which SNCC organizers Sherrod and Reagan were determined to penetrate. Sherrod says:

When we first came to Albany, the people were afraid, really afraid. Sometimes we’d walk down the streets and the little kids would call us Freedom Riders and the people walking in the same direction would go across the street from us, because they were afraid; they didn’t want to be connected with us in any way. . . . Many of the ministers were afraid to let us use their churches, afraid that their churches would be bombed, that their homes would be stoned. There was fear in the air, and if we were to progress we knew that we must cut through that fear. We thought and we thought . . . and the students were the answer.

There was one institution of higher education in town, Albany State College for Negroes. Reagan and Sherrod began visiting the campus, talking to the students, who had begun to stir early in 1961 when marauding whites in automobiles raced through the campus, throwing eggs, firing guns, and once trying to run down a Negro girl. Protesting against this, the students had found themselves up against the conservatism of a Negro college president, dependent for his job on the Board of Regents of the State of Georgia. The Dean of Students at Albany State was a militant young woman named Irene Asbury Wright, married to an Air Force lieutenant stationed in Albany. She sided with the students, and then resigned in protest against the administration’s repressive policies. Sherrod described in his own way the situation he and Reagan found when they began to organize the students:

There is a school in Albany, Albany State College, where the minds of young men and women are not free to reason for themselves what is most important in life. They are “protected from” all seduction to think on what it means to be a black man in Albany or anywhere else in the South. . . . The campus is separated from the community by a river, a dump yard and a cemetery. And if any systems of intelligence gets through all of that it is promptly stomped underfoot by men in administrative positions who refuse to think further than a new car, a bulging refrigerator, and an insatiable lust for more than enough of everything we call leisure. . . .