By Howard Zinn • The Progressive • February 3, 2003

By Howard Zinn • The Progressive • February 3, 2003

The long funeral procession for Phil Berrigan moved slowly through the streets of the poor black parish in Baltimore where he had begun his priesthood. Some parents held young children by the hand, as they walked behind the flatbed truck that carried Phil’s coffin, which had been made by his son, Jerry, and was decorated with flowers and peace symbols.

It was a bitterly cold December day in the kind of neighborhood where the city doesn’t bother to clear the snow. People looked on silently from the windows of decaying buildings, and you could see the conditions that first provoked Phil’s anger against the injustice of poverty in a nation of enormous wealth.

Some thousand people crowded into the church. A young priest, a friend of the Berrigans, dressed in white clerical robes, officiated. The service was suffused with religious solemnity–Buddhist chants, church hymns, prayers–and in the background the soft sounds of children, while all around were colorful posters and paintings: No More War, Peace Is the Way.

Phil’s wife, Elizabeth McAlister, son Jerry, and daughters Frida and Kate spoke lovingly, eloquently, of their father. Daniel Berrigan, priest, poet, and brother, read one of his poems. Bread and wine were handed out.

Someone read the statement Phil dictated to Liz when he was unable to hold a pen. He spoke of his community in Jonah House in Baltimore. “They have always been a lifeline to me.” He knew the end was near, but was unwavering in his commitment: “I die with the conviction that nuclear weapons are the scourge of the Earth; to mine for them, manufacture them, deploy them, use them, is a curse against God, the human family, and the Earth itself.”

Phil Berrigan was a hero in a time when we cannot find heroes among the politicians in Washington, much less the timorous press.

The real heroes are not on national television or in the headlines. They are the nurses, the doctors, the teachers, the social workers, the janitors, the hospital orderlies, the construction workers, the people who keep the society going, who help people in need. They are the advocates for the homeless, the students asking a living wage for the campus janitors, the environmental activists trying to protect the trees, the air, the water. And they are the protesters against war, the apostles of peace in a world going mad with violence.

Among these was Philip Berrigan. Phil was a priest who defied his church by marrying his sweetheart, a former nun. He defied his government by challenging its accumulation of nuclear weapons, its death-dealing wars in Southeast Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. And he went to prison again and again because he committed civil disobedience–pouring blood on nuclear warheads, hammering away at America’s weapons of mass destruction.

He saw combat as an infantryman in World War II and came away from that war with the belief that war does not solve the fundamental problems that face the human race. As a young Catholic priest, he worked among poor black people in Baltimore, and he became convinced that racism and poverty were intertwined. He was an early opponent of the war in Vietnam, and he believed, as Martin Luther King Jr. said, that “the evils of capitalism are as real as the evils of militarism and the evils of racism.”

I came to know Phil Berrigan well, at first through his brother. Dan and I became good friends when we flew to Hanoi during the Tet Offensive of January 1968 to bring back three American airmen, whom the North Vietnamese had decided to release from prison as a goodwill gesture for the Tet holiday.

It was shortly after our return that Dan joined his brother Phil and seven others in a dramatic protest against the war. They invaded the selective service office in Catonsville, Maryland, pulled draft files out of their cabinets, piled them outside, and set them afire with homemade napalm. The protesters, immediately arrested, became known as the Catonsville Nine.

They were calling attention to the burned children of Vietnam, victims of the napalm dropped by American planes.

Dan Berrigan wrote, in advance of the Catonsville action: “Our apologies, good friends, for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children. How many must die before our voices are heard, how many must be tortured, dislocated, starved, maddened? When, at what point, will you say no to this war?”

They were convicted and sentenced to several years in jail. When their appeals were exhausted, Phil Berrigan and Dan Berrigan refused to give themselves up and went into hiding. They believed in continuing the civil disobedience they had begun.

It was at this point that I was invited to speak at an anti-war rally at a Catholic church on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. When I arrived, I found that the FBI had smashed its way into the priest’s quarters, where Phil Berrigan was hiding, and had taken him into custody. Dan Berrigan remained underground for four months (during which time I and some friends helped him move about in the Boston area) before he was apprehended.

My wife, Roslyn, and I visited Phil and Dan as they were serving time in Danbury Prison. When they were released after several years, they continued to protest against the war in Vietnam. And when the war was over, Phil, Dan, Liz, and their community of religious pacifists did not stop.

In 1980, they carried out the first of what would be dozens of “Plowshares” actions, symbolic sabotage against nuclear weapons. There were many trials, many jail terms.

Altogether, Phil Berrigan served more than ten years in various prisons for his passionate insistence that war was a cruel response to the problems people faced in this country and around the globe.

It was not long after his release from his last prison sentence that he was diagnosed with kidney and liver cancer. Four months later, he died. To the end, he was nurtured by the community of men and women who lived together for years in Jonah House, sharing their possessions, caring for the children when the parents were in jail.

Philip Berrigan was imprisoned again and again because he wanted peace. He is gone now. But his struggle is carried on by Liz, by their three children, and by the extraordinary community of fellow lawbreakers in Jonah House and neighboring Viva House (holy outlaws, Dan Berrigan once called them).

Brendan Walsh and Willa Bickham at Viva House–former priest and former nun, now married–spoke at the funeral. Brendan said what everyone felt: “Philip Berrigan is a friend to all the poor of Baltimore City. Philip Berrigan is a friend to all the people of the world who are bombed and scattered, who are starved, trampled upon, imprisoned, tortured, humiliated, scoffed at, dismissed as nobodies. He was that rare combination where word and deed were one. Always. Everywhere. Steadfast. Rock solid. Hopeful. One in a million. He was that tree standing by the water that would not be moved. Yes, Phil, Deo gratias! Thanks be to God! For your life. For your spirit that is still with us. Now, with you gone to another place, all of us will have to do more. Couragio to you, Phil!”

Countless people all over the nation, and in other parts of the world, will remember Phil Berrigan as one of the heroes of our time–along with Gandhi, A. J. Muste, Dorothy Day, Martin Luther King Jr. They and so many others, not famous, who have struggled against war, who have tried to live the principles of a loving community, teach us what heroism is.

Published in The Progressive • February 3, 2003

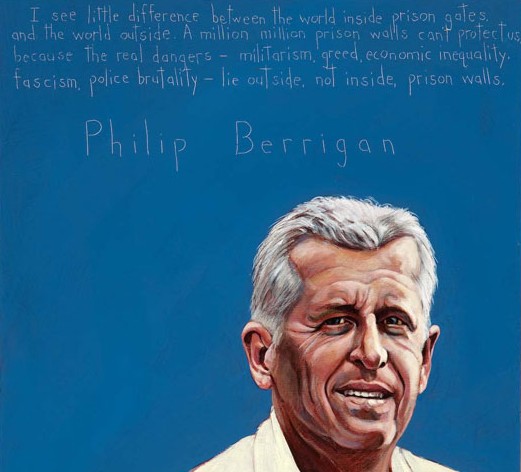

Photo/image: Philip Berrigan Poster by American Who Tell the Truth